Test-driven development and data science

The previous two posts of this series were about the business and people perspectives of effective data science teams. However, in themselves they are only necessary but sufficient conditions: without the right tools and processes, the recipe does not work.

Therefore, in the next parts, I’m going to discuss some of the tools and processes that I consider important for a data science team. This part is about how to consolidate the practices of data analysis with the practices of software development. The specific part that I’m going to focus on is test-driven development (aka. TDD) for data analysis.

At first, I intended this also as a post around stories and conclusions, like the previous ones. But since I did not find any good tutorials online that would explain TDD from scratch to a working model, I’ve decided to make one myself to supplement this post. If you are familiar with TDD and would like jump right to the tutorial then click here. In the following, I introduce shortly TDD, the reasons why I think TDD is useful in data analysis, and then I conclude with a complete step-by-step TDD workflow using an example project from Kaggle.

Test-Driven Development

Test-driven development is popularized by Kent Beck, the father of extreme programming. It helps development teams to focus on the required features and helps rapid iteration of versions. The main idea is that when you think of a new feature that you have to add to the code, first add a test that expects that feature to be present and see it FAIL. Then, write the quickest solution to PASS this test. Once it was passed take some time to REFACTOR the code. All three parts of the process are equally important and they work best in this order.

Take for example the first step: fail. I remember when some time ago, we were sitting in front of the computer with my colleagues and were looking at why changing the input parameters of a function does not change the output in an expected way although there was a unit test covering exactly that function. After some investigation, it turned out that the mentioned unit test, which I wrote after the function was created, could actually never fail.

The next important thing is to focus on only passing the actual test and not writing code that is intended to pass all possible tests in the future. One mantra helping in this is to ‘Keep it simple, stupid’ (KISS) that is often written on the wall of an IT office. Serious TDD practitioners literally stop as soon as the test passed and switch writing the next test if no refactoring needed. This yields short cycles of fail-pass iterations (aka. the flow). Also, the refactoring should not mean changing the test logic or completely rewriting the function that passed it. If you feel for example that the function is duplicated or has too many parameters then refactor.

Test-driven development reduces the time for maintenance if you have time in between maintenance tasks to switch to test-driven development.

Test-driven development reduces the time for maintenance if you have time in between maintenance tasks to switch to test-driven development.

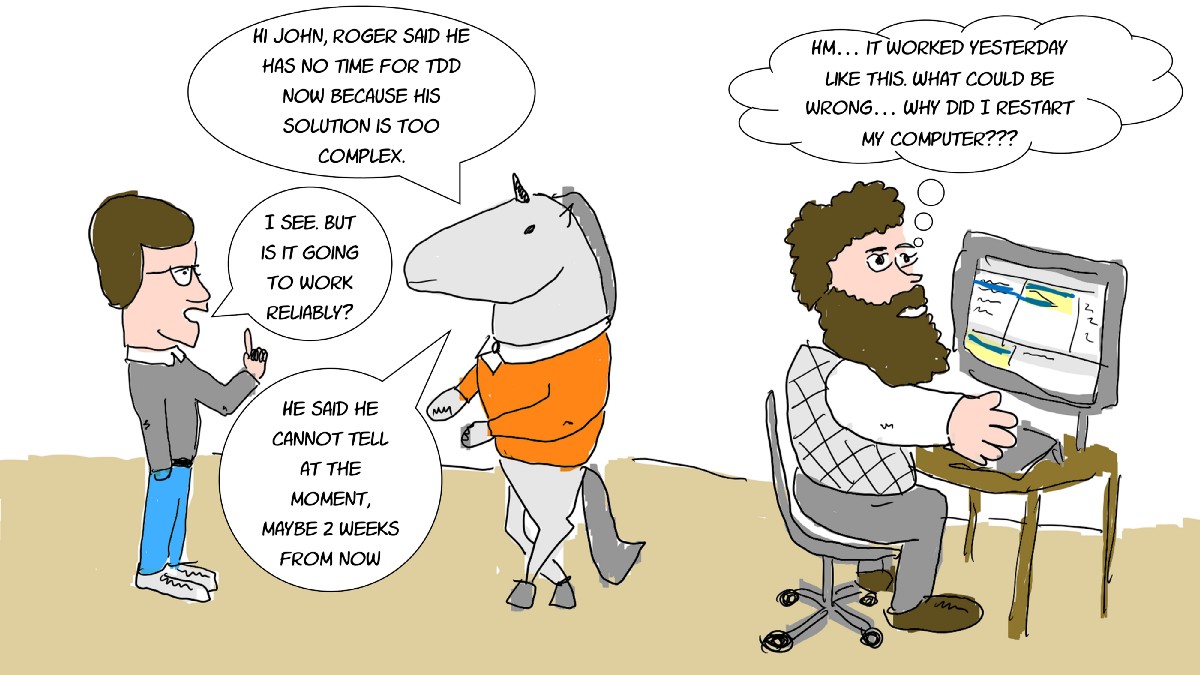

TDD for analytics

Now, one can say: alright this is nice and true for writing software for production but how does it relate to my practice when I do exploratory data science. First, I’m sure you met the situation when something that you calculated in your notebook in — let’s say — Jupyter is not working in the next stage of the development. Maybe the fields were not matching, maybe the datatypes, or maybe a seed was not fixed. Second, it should sound familiar when the data just drags you down into the rabbit hole: you notice that a linear model does not explain enough variance so you try some non-linear ones, then you see also that some missing values can be predicted so you predict those, then you see that maybe the data should be transformed, some string columns should be vectorized, others should be levels of an ordinal scale etc. Then, 2 weeks into the exploration the manager asks where is the result that you promised for one week ago and you can only explain to him what will be your next steps… And you still did not reduce the uncertainty for her. And she still does not know if the feature/model is needed at all or we should concentrate on other promising directions.

And third, there is craftsmanship in data science as well. Although we read about the nice new discoveries in machine learning, the researchers that made those discoveries had to follow a rigorous stream of steps before they even had a chance to try out something new. They had to follow the principled way of data access, cleaning, transforming, modelling, and validation, which we all follow. Nevertheless, this is a very complex process with lots of things to pay attention to. TDD helps in keeping these steps modular. It facilitates replication, extension, and falsification. There are even libraries that aim at providing some general tests to help out practitioners.

On top of these empirical considerations, there are theoretical ones as well. TDD and scientific methodology are very similar. When you create a test and see it failing is basically making a scientific hypothesis that is falsifiable. When you pass the test that is basically equivalent to the statistical testing of your experimental manipulation in a research study. Finally, refactoring is similar to the function of the discussion part of a paper: you turn your experimental manipulation to a theory.

John has to remember that agility comes with a price.

John has to remember that agility comes with a price.

Testing Sanity and Insanity

Although software testing has its own jargon (unit, integration, system testing), I consider for some time another way of looking at tests that drive your development. I think about tests of insanity and sanity. Testing insanity means that you want to make sure that the feature that you created is not producing non-sensical results. For example, it gives some result for input A and some other result for input B, that is it is not insane. You also want to make sure that your model is trained, that it expects the right features and outputs in the expected range. However, no client is going to pay for a solution that is guaranteed to be not insane. This is only a necessary but not sufficient condition. For that our solution has to be sane. Therefore sanity testing assesses some higher level and even abstract hypotheses; e.g. that your solution (take a deep neural network) is better than a simple arithmetic average or that you are not overfitting the training data.

These are features that can be translated easily into direct business value. Financial software requires very strong arguments to choose a deep learning solution over an interpretable model when they can lose huge money instantly with a bad decision. Also, when you are already overfitting the training data when you compare it to the validation sets then imagine the how much difference you are going to see between the expected and the real fit for a dataset that was collected in a later batch. The way I think about these it: passing sanity tests sell your model passing insanity tests warrants customer satisfaction in the upcoming months and years of using your model.

Now let’s take a practical tone. As they say, it is often difficult to tell the fine line between a madman and a genius. The same goes for the question of ‘should I put this test in the insanity or in the sanity bucket?’. So, at this point, it is time to delve into the step-by-step tutorial. I took an example dataset from Kaggle, the House Prices dataset this is a sufficiently easy and fun data. Just right to pass the imaginary test of ‘tutorial on TDD for analysis’.